Who was Barry?

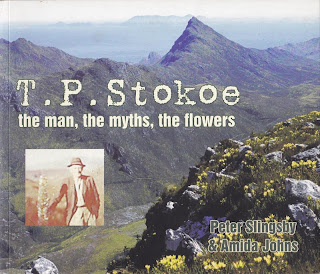

I recently came across an interesting review* in the South African Journal of Science by historian Lance van Sittert of one of my favourite books, T.P. Stokoe: The man, the myths, the flowers by Peter Slingsby and Amida Johns.

Van Sittert, an environmental historian in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town, draws attention to the intimacy that Thomas Pearson Stokoe developed with the Adderley Street and Sir Lowry's Pass flower sellers and pickers, a friendship that yielded many amazing and new finds which the working class Yorkshireman then handed over to the taxonomists for scientific recording. Van Sittert quotes from the book, quoting Stokoe: ‘Flower-pickers are professional mountaineers. With a hunk of bread, some coffee, a can, a roll of hessian and a riempie they are equipped for a few days wandering amongst the flower-clad regions of the mountains. When not doing a solo trip I always engage them. They can carry weight over rough and awkward country, they know the caves for wet weather, and when the heaviest of dew falls I have crept out of my tent like a frozen shrimp to find that they have slept warm and dry under the stars by the simple method of lying in the lee side of a few low-burning logs’.

The reviewer goes on to say, that 'Stokoe’s intimacy with, and sympathy for, the city’s Black flower sellers and pickers would have set him radically apart from his fellows in the Botanical Society and Mountain Club in the era of segregation and apartheid, but was in the tradition of the old imperial botanical travellers, who he further emulated in labour exerted, dangers endured and successes achieved.' He explored the Kogelberg, and 'of the 245 botanical collecting trips he made over the next 40 years, two-thirds were to these mountains. Altogether, they yielded an astonishing harvest of nearly 20 000 specimens, of which 130 were new to science (no fewer than 30 being named after him), with the prospect of still more to come from the enormous backlog of nova species still awaiting processing in the incertae sections of the various Cape Town and other herbaria he endowed. TP’s reputation made him a prized collector for Marloth, the city’s public herbarium at the South African Museum, the Bolus Herbarium at the University of Cape Town, and later the National Botanical Garden at Kirstenbosch, as well as those further afield in Pretoria and, of course, at Kew. He also generously endowed the botanical gardens at Kirstenbosch and Kew with seeds, cuttings and even plants gathered on his journeys.'

Van Sittert praises the book for bringing the life and works of this energetic man to the fore - a man whom many botanists of the day looked down on. Professor Compton, the Cambridge-educated Director of Kirstenbosch from 1919 to 1954, 'always pointedly excluded TP from his field trips.'

Van Sittert goes on to say that 'Whatever Compton’s class antipathy towards the working class Yorkshireman, Stokoe’s open fraternisation with, and admiration for, Black flower pickers would have made any close association difficult for Compton in the context of segregation and the Botanical Society members’ longstanding jihad against the city’s wild flower trade. Compton’s successor, H.B. Rycroft, was more welcoming of Stokoe, but only to exploit him as an oddity – the ‘Grand Old Man’ of Cape botany – for publicity purposes.'

Van Sittert then chastises the authors for not trying to find out more about Stokoe's flower seller friends and guides, especially the enigmatic Barry of his letters. 'For all that Slingsby and Johns claim to be dispelling "myths" about Stokoe (by which they mean errors of fact), their book, in its failure to follow-up on his relationship with the Black flower pickers, perpetuates one of its own about him (and Cape botany). It is a myth, one suspects, that is dear to the hearts of its (amateur botanist) authors: that of White amateur botany as heroic individual endeavour and equal to science in the field of taxonomy.' Ouch!

Read the full review here.

*Van Sittert, L. The intimate politics of the Cape Floral Kingdom. S Afr J Sci.2010;106 (3/4), 162.

Van Sittert, an environmental historian in the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Cape Town, draws attention to the intimacy that Thomas Pearson Stokoe developed with the Adderley Street and Sir Lowry's Pass flower sellers and pickers, a friendship that yielded many amazing and new finds which the working class Yorkshireman then handed over to the taxonomists for scientific recording. Van Sittert quotes from the book, quoting Stokoe: ‘Flower-pickers are professional mountaineers. With a hunk of bread, some coffee, a can, a roll of hessian and a riempie they are equipped for a few days wandering amongst the flower-clad regions of the mountains. When not doing a solo trip I always engage them. They can carry weight over rough and awkward country, they know the caves for wet weather, and when the heaviest of dew falls I have crept out of my tent like a frozen shrimp to find that they have slept warm and dry under the stars by the simple method of lying in the lee side of a few low-burning logs’.

The reviewer goes on to say, that 'Stokoe’s intimacy with, and sympathy for, the city’s Black flower sellers and pickers would have set him radically apart from his fellows in the Botanical Society and Mountain Club in the era of segregation and apartheid, but was in the tradition of the old imperial botanical travellers, who he further emulated in labour exerted, dangers endured and successes achieved.' He explored the Kogelberg, and 'of the 245 botanical collecting trips he made over the next 40 years, two-thirds were to these mountains. Altogether, they yielded an astonishing harvest of nearly 20 000 specimens, of which 130 were new to science (no fewer than 30 being named after him), with the prospect of still more to come from the enormous backlog of nova species still awaiting processing in the incertae sections of the various Cape Town and other herbaria he endowed. TP’s reputation made him a prized collector for Marloth, the city’s public herbarium at the South African Museum, the Bolus Herbarium at the University of Cape Town, and later the National Botanical Garden at Kirstenbosch, as well as those further afield in Pretoria and, of course, at Kew. He also generously endowed the botanical gardens at Kirstenbosch and Kew with seeds, cuttings and even plants gathered on his journeys.'

Van Sittert praises the book for bringing the life and works of this energetic man to the fore - a man whom many botanists of the day looked down on. Professor Compton, the Cambridge-educated Director of Kirstenbosch from 1919 to 1954, 'always pointedly excluded TP from his field trips.'

Van Sittert goes on to say that 'Whatever Compton’s class antipathy towards the working class Yorkshireman, Stokoe’s open fraternisation with, and admiration for, Black flower pickers would have made any close association difficult for Compton in the context of segregation and the Botanical Society members’ longstanding jihad against the city’s wild flower trade. Compton’s successor, H.B. Rycroft, was more welcoming of Stokoe, but only to exploit him as an oddity – the ‘Grand Old Man’ of Cape botany – for publicity purposes.'

Van Sittert then chastises the authors for not trying to find out more about Stokoe's flower seller friends and guides, especially the enigmatic Barry of his letters. 'For all that Slingsby and Johns claim to be dispelling "myths" about Stokoe (by which they mean errors of fact), their book, in its failure to follow-up on his relationship with the Black flower pickers, perpetuates one of its own about him (and Cape botany). It is a myth, one suspects, that is dear to the hearts of its (amateur botanist) authors: that of White amateur botany as heroic individual endeavour and equal to science in the field of taxonomy.' Ouch!

Read the full review here.

*Van Sittert, L. The intimate politics of the Cape Floral Kingdom. S Afr J Sci.2010;106 (3/4), 162.

Comments